The Noble Qur’an Reads: “And by the Earth that has its own fault” (86:12). This Qur’anic verse comes in the context of an oath, while Allah (all glory be to Him) is definitely above giving such a pledge. Consequently, this is understood as an emphasis for the special significance of the matter by which the oath is given.

What is the special significance of the faults of our planet?

Early commentators on the Holy Qur’an saw this significance in the fracturing of the soil on watering it properly to give a free, safe passageway for the tender, green shoots coming out from the germinating seeds that are buried in the soil, in the form of sprouting plants, which is very true.

Once you place a seed in the soil and water it properly, it starts to germinate and a green shoot starts to penetrate the soil and grow into a fully developed plant, bearing beautiful flowers, delicious fruits or vegetables, and/or magnificent wood. Such penetration takes place through tiny fractures that develop in the soil as a result of its inflation by hydrolysis and warping upwardly until thinning out to the point of fracturing.

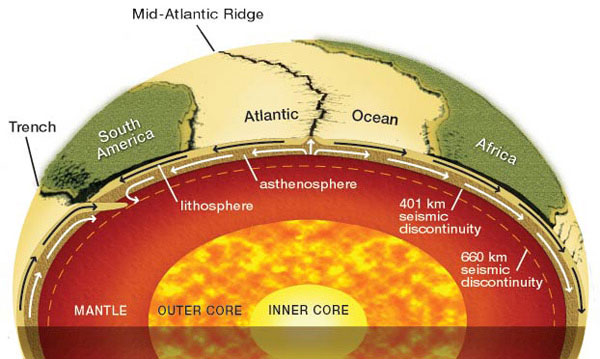

However, Earth Scientists have recently discovered that the Earth’s outer rocky sphere (Lithosphere; which is about 65-70 km thick under the oceans and 100-150 km thick under continents) is broken up by a network of deep faults or rift systems into 12 main rigid plates, added to a number of small ones (microplates or platelets).

These plates float on a semi-molten plastic layer known as the asthenophere (the sphere of weakness) and move freely away from or towards each other, and past one another. At one boundary of each plate (or microplate), molten rock (magma) rises to form strips of new ocean floor, and at the opposite boundary, the plate collides with the adjacent plate and moves to sink underneath it, to be gradually consumed in the underlying asthenophere at exactly the same rate of sea-floor spreading at the opposite side.

An ideal, rectangular, lithospheric plate would thus have one edge growing at a mid-oceanic rift system (divergent boundary), an opposite edge being gradually consumed into the asthenophere, below the over-riding or colliding plate (convergent boundary) with the other two edges sliding past the adjacent plates along a system of transform faults (transcurrent or transform fault boundaries).

In this way, the lithospheric plates are constantly shifting position on the surface of the globe, despite their rigidity, and as they are carrying continents with them, such continents are also constantly drifting away or towards each other.

As an oceanic lithospheric plate is forced under another oceanic or continental plate and its descending part starts to melt, viscous magmas are intruded and squeezed between the colliding plates, while lighter and more fluid ones are extruded at the opposite edge to form island-arcs. These eventually grow into subcontinents and continents, are plastered to the margins of nearby continents, or squeezed between two colliding continents.

Such divergence, convergence and sliding of lithospheric plates are not confined to ocean basins, but are also found along the margins, as well as within and in between continents.

Both the Red Sea and the Gulf of California troughs (which are extensions of oceanic rifts) are currently widening at the rates of 3cm/year and 6cm/year respectively.

On the other hand, the collision of the Indian Plate with the Eurasian Plate, after the consumption of the oceanic plate that was separating them, resulted in the formation of the Himalayan Chain, with the highest peaks on the surface of the Earth today.

Fault planes traversing the outer rocky sphere of the Earth for tens of thousands of kilometers across the globe, running in all directions for a depth of 65-150 km are among the most salient features of our planet.

These came to human notice only after the Second World War and were only understood within the framework of the concept of plate tectonics which was finally formulated in the late sixties and the early seventies of this century (cf. Hess, 1963; Morely, 1963; Wilson, 1965; McKenzie, 1967; Maxwell and others, 1970; Cox, 1973; Le Pichon and others, 1973; Dennis and Atwater, 1974, etc.).

These lithospheric faults are a globe-encircling system of prominent rift zones (65-150 km deep and tens of thousands km long) along which lithospheric plates are displaced with respect to one another divergently, convergently or sliding past each other. They are also passageways through which the trapped heat below the lithosphere is steadily released, and different magmas are steadily outpouring.

Molten magmas in numerous hot spots, deep in the mantle, being less dense, tend to rise up and descend down on cooling in the form of hot plumes that create convection currents. Such currents carry the lithospheric plates and move them across the globe, with divergent, convergent, and sliding relationships.

Divergence takes place at the rising tips of the convection current, while convergence takes place at its descending sides.

During the early history of the Earth, its interior was much hotter (due to the greater amount of residual heat of accumulation and the much greater amounts of radioactive isotopes such as 235U and 40K) and hence convection was much faster and so were all the phenomena associated with it {such as volcanic activity, earthquakes, plate movements, mountain-building movements and continental build-ups, (or the so-called ocean-continent cycle or the geosynclinal/mountain-building cycle), etc.}.

During these processes, both the atmosphere and the hydrosphere of the Earth were outgassed, the continents were constructed as positive areas above the ocean basin (through the accretion of volcanic island arcs into sub-continents and continents) and mountains were built.

About 500 million years ago the early continents were dispersed across the surface of the Earth, in positions much different from the ones occupied by the continents of today. Convection currents then operating in the mantle ended up pushing all the early continents together around 200 million years ago, into a single super-continent (Pangea) above a single super-ocean (Panthalassa).

The outer rocky sphere of the Earth (or lithosphere) acted as a lid, impeding heat flow from inside the Earth. The trapped heat produced a great rift system right in the middle of the mother continent, and this rift system propagated gradually though time, separating North America from North Africa (about 180 million years ago) and from Europe (about 150 million years ago), followed by separating South America from Africa (about 110 million years ago) and separating Greenland from Norway (about 65 million years ago), when Iceland began forming.

When this break-up of Pangea began, a westward waterway from the mother ocean (Panthalassa) in the form of a broad gulf (called Tethys) encroached gradually over Pangea, breaking it into a northern continent (Laurasia) and a southern one (Gondwana).

Further fragmentation produced the present continental masses, which are currently undergoing more breaking up. The original rift is now the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, whose axis is still an active site of basaltic outpourings similar to many other rift zones along which current sea-floor spreading is taking place (cf. El-Naggar, Z.R., 1991, p. 42-45 and Emiliani, C., 1992: p 237, 238).

Basaltic material has been pouring out gradually from more than 64,000 km of mid-ocean rift valleys on both sides of such ruptures in the Earth’s crust, since the very early days of their formation. The youngest oceanic crust is always around the deep rift valley and has steadily been pushing older crusts away from it.

The age of the oldest existing oceanic crust doesn’t exceed the Mesozoic era (about 200 million years old), and is currently being consumed at the convergent edges of the plates with rates almost equivalent to the rate of producing new oceanic crust at the mid-oceanic ridges.

Volcanic mountains are also found on the continents such as the isolated peaks of Mount Ararat (5100m above sea level), Etna (3300m), Vesuvius (1300m), Kilimanjaro (5900m) and Mount Kenya (5100m).

These are associated with intra-cratonic, deep rift systems that traverse the whole thickness of the lithosphere, and communicate with the asthenosphere, and hence are currently fragmenting the existing continents into smaller landmasses.

From the above mentioned discussion, it becomes obvious that the magnificent network of deep fault systems (65-150km deep) that encircle the globe for tens of thousands of kilometers in all directions {breaking its outer rocky zone (the lithosphere) into major, lesser and minor plates, microplates (or platelets), plate fragments and remnants} is one of the most striking realities of our planet.

Without these deep fault systems the Earth could not possibly have been inhabitable. This is simply because of the fact that it is through such deep faults that both the atmosphere and the hydrosphere have been outgassed and are constantly rejuvenated, continents are steadily built and fragmented, mountains are constructed, the crust is periodically enriched with new minerals, lithospheric plates are moved, the accumulating internal heat of the Earth is gradually and steadily released and the whole dynamics of our planet are achieved.

Consequently, such as established fact of the Earth is so vital for its existence as well as for our own survival on its surface that it becomes well deserving to be mentioned in the Glorious Qur’an as one of the signs of The Creator. However, such a fact didn’t attract the attention of Earth scientists until after the Second World War, and wasn’t fully understood until the late sixties and the early seventies of this century.

The Qur’anic precedence of such an established salient feature of the Earth more than 14 centuries ago is one of numerous signs that clearly testify for the purely Divine nature of this illustrious Book, and for the truthfulness of the Prophethood of Mohammad (PBUH).

This article was first published in 1999 and is currently republished for its importance and uniqueness.