Clear Roles & Responsibilities

Furthermore, in terms of scopes and jurisdictions, there should be neither ambiguities nor encroachments. People should be clear (and educated accordingly) about this and should be primed for performance. As for instance, men in their roles cannot try to imitate, nor hinder, those of women, and vice versa.

The place and roles of youth should be defined properly and empowered as well. In fact, they should be thrust into the limelight – just as the condition of Isma’il had been – because they are the future. As should the compasses of people’s individual and collective, official and unofficial, duties be clearly outlined. The basis should be a social contract, and the culture cooperation.

Islam does not advocate any sort of imbalance, bias, preferentialism and even equality of the sexes, in the sense of the ideology of feminism. Rather, it advocates equity, impartiality and inclusivity. In order to expect everybody to be productive and behave accountably, everybody must be given equal access to opportunities and resources first. A community should be turned into a vibrant entity whose parts are held together in unity and strength, “each part contributing strength in its own way, and the whole held together not like a mass but like a living organism.”[1]

The Prophet (peace be upon him) said:

“Each of you is a shepherd and each of you is responsible for his flock. The amir (ruler) who is over the people is a shepherd and is responsible for his flock; a man is a shepherd in charge of the inhabitants of his household and he is responsible for his flock; a woman is a shepherdess in charge of her husband’s house and children and she is responsible for them; and a man’s slave is a shepherd in charge of his master’s property and he is responsible for it. So each of you is a shepherd and each of you is responsible for his flock.”[2]

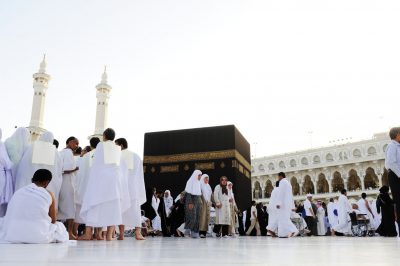

History of Sa’y Location

Mas’a – the location and route of sa’y – lay outside the precincts of the Holy Mosque (al-Masjid al-Haram). There were private houses and institutional buildings that separated the two. Mas’a was quickly turned into a main street (boulevard) of Makkah, lined with houses and shops. It became a commercial hub of the city too. During the Prophet’s time, the segment of mas’a where pilgrims are required to run was part of a dried riverbed covered with small stones, and the Prophet (peace be upon him) instructed:

“The riverbed is not crossed except with vigour.”[3]

This situation persisted until the expansion of the Holy Mosque by the third Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi (d. 785) when all the land with its built environment between the Mosque and mas’a was annexed and cleared for the construction. The south-eastern section of the Mosque linked up afterwards with a mas’a section that was close to Safa. However, the mas’a stretch was yet to be integrated into the Mosque proper. That was done only in modern times, during the first Saudi expansion in 1955 by King Sa’ud b. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz (d. 1969).

When Eldon Rutter (Ahmad Salahuddin al-Inklizi) (d. 1956) – an English reclusive explorer – performed his Hajj in 1925, he wrote about mas’a that it was lined for more than half its length with little shops, and the part in which those shops were situated was roofed over. This roof extended from Marwah to the Dar al-‘Abbas. The mas’a street, which was one of the principal markets of the city, was still unpaved in 1925. However, the author remarked that he had heard that the newly-crowned King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz bin Al Sa’ud had given orders that mas’a must be paved with stone at the earliest possible time.

Eldon Rutter added: “During my time in Mekka, it (mas’a) was always several inches deep in dust or mud, according to the season of the year. In dry weather, the crowds which constantly passed to and fro, shopping or performing the sa’y, stirred up a thick fog of dust which made breathing extremely uncomfortable.”[4]

The state of mas’a throughout history calls to mind a contention that sa’y stands predominantly for the worldly energy and movement. It is a symbol of the straight path that leads to the success of this world and the Hereafter. But the path and the mission of treading it are fraught with trials lurking on all sides, which nonetheless vary in scale and magnitude. So engrossed in his duty should a person be that he will not be bothered, much less turned away from the path. Moving with vigour and frequently running, with no time to be idle and lose focus as well as perspective (sa’y), helps a person to stay the course and never lose sight of his goals.

This does not mean that mas’a actually featured any of those trials and challenges – above all major ones – however its several disturbances, natural and man-made, rang a bell as little as emblematically. Towards the end of this construal is the following hadith of the Prophet (peace be upon him). A companion Abdullah bin Mas’ud reported:

“The Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) drew a line in the sand with his hand and said: “This is the straight path of Allah.” Then, he drew lines to the right and left, and said: “These are other paths, and there is no path among them but that a devil is upon it calling to its way.” Then the Prophet (peace be upon him) recited the verse: “Verily, this is the straight path, so follow it and do not follow other ways” (al-An’am, 6:153).”[5]

(To be continued…)

Part 1 – The Spirituality of Hajj: An Introduction

Part 2 – The Spirituality of Hajj: Ihram and Talbiyah

Part 3 – The Spirituality of Hajj: Tawaf

[1] Abdullah Yusuf Ali, The Holy Qur’an, English Translation of the Meanings and Commentary, https://islamic1articles.home.blog/2019/01/02/quran-tafsir-yusuf-ali-chapter-wise-pdf/, accessed on January 31, 2022.

[2] Abu Dawud, Sunan Abi Dawud, Book 20, Hadith No. 1.

[3] Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani, Rites of Hajj and ‘Umrah from the Qur’an, Sunnah and Narrations from the Pious Predecessors, www.islamhouse.com, 2010, accessed on January 31, 2022.

[4] Eldon Rutter, The Holy Cities of Arabia, (London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons LTD, 1928), vol. 1 p. 113.

[5] Al-Tabrizi, Mishkat al-Masabih, Book 1, Hadith No. 160. Ibn Majah, Sunan Ibn Majah, Introduction, Hadith No. 11.

Pages: 1 2